The U.S. House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) Minority yesterday released roughly 3,400 ads that ran on Facebook and Instagram leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential elections

“There’s no question that Russia sought to weaponize social media platforms to drive a wedge between Americans, and in an attempt to sway the 2016 election,” said Representative Adam Schiff, Ranking Member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, in a statement. “Russia sought to divide us by our race, by our country of origin, by our religion, and by our political party.”

The Nature of the Ads

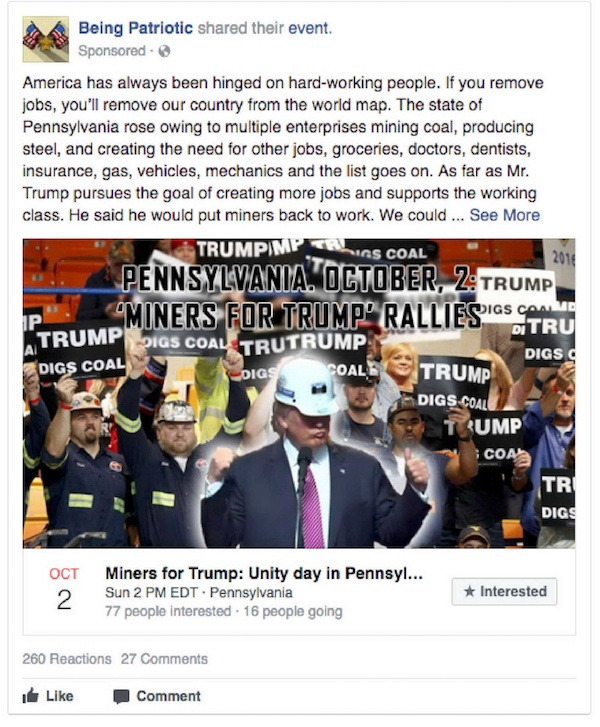

We combed through as many of the ads as we could, and based on the sample we viewed prior to publishing this post, they accurately reflect Schiff’s statement.

The ads represent only a portion of what has been reviewed by the HPSCI Minority over the course of its investigation of Russian interference with U.S. electoral processes.

In addition to these ads, the Minority noted in a statement that many of these IRA-created accounts — which purchased the ads — also published 80,000 pieces of organic content, which

That content was not included in what was released yesterday, and its nature remains unclear. As for the ads, the Minority states that they were exposed to over 11.4 million American Facebook and Instagram users.

The IRA-purchased ads focus on a range of issues to a somewhat superficial degree, including:

- Race

- Police Brutality

- Patriotism

- Civil Rights

- Sexual Orientation

- Immigration

- Economy

Without looking at every single ad, it’s difficult to say if a majority of them leaned to one particular political aisle. For many of the above-listed issues, there were accounts created and ads published for both sides.

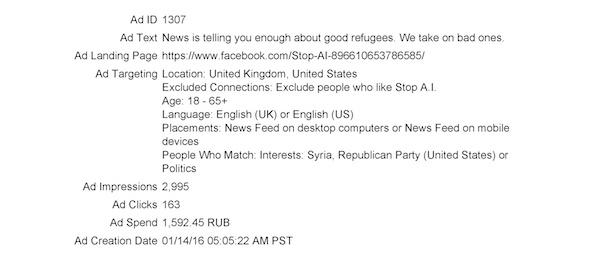

On the issue of refugees, for example, each of the below pages (and the ads bought to promote them) appears to take a contrasting side — yet both were the work of the IRA.

Some of the ads contained information and images that were redacted “to protect personally-identifiable information (PII),” according to a statement released by the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.

Many of the ads were also purchased to promote events falling on either side of contentious issues. In addition to certain content redactions, the Minority says it has urged Facebook to inform creators of “genuine online events” that they might have been unknowingly advertised by the IRA.

In addition to those redactions, the statement notes that Facebook notified users whose genuine online events were unwittingly promoted by the IRA.

The nature of the ads released by Congress seems to be overwhelmingly issue-based, most of them not pertaining to a certain candidate but rather emphasizing topics that are often sources of debate and divisiveness — especially during election season.

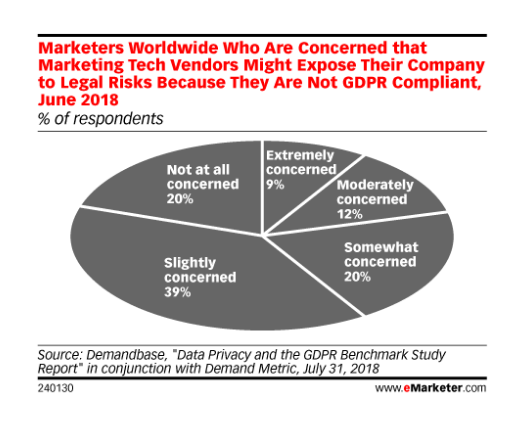

In October, Facebook introduced a verification process that would only allow authorized advertisers to run electoral ads on Facebook or Instagram — that is, ads for a specific candidate — and will also contain a “Political Ad” label.

That same process will apply to those seeking to publish issue-based ads, though

Other ads are completely irrelevant to the most hotly contested issues during elections, such as those from an account called

0003820.jpg?t=1526105585958&width=450&name=P(1)0003820.jpg)

Nonetheless, a number of ads do focus on specific political and former presidential candidates, sharpening the

0003842-1.jpg?t=1526105585958&width=350&name=P(1)0003842-1.jpg)

0003842(2).jpg?t=1526105585958&width=450&name=P(1)0003842(2).jpg)

That targeting information is crucial — and where the ads become most complicated.

The Targeting

Alongside images of the ads themselves, the HPSCI Minority also released the following details of each ad:

- The ad’s ID number

- The text that ran with the ad

- A link to the ad’s landing page

- The age, language, and location of the ad’s target audience

- The ad’s impressions, clicks, spend, and date of creation

In April, Facebook announced that it would be creating a public, searchable archive of political ads containing similar information to the PDFs released.

What we found particularly interesting was the nature of the targeting criteria for each ad. Facebook’s targeting tools allow advertisers to build a customized audience for promoted content, based on interests, location, age range, and other demographic information.

The IRA appears to have used these tools to its advantage, targeting each one to an audience with which it thought the somewhat polarizing content would resonate the most. For instance, here’s the targeting information for the ad promoting the “Stop A.I.” page above:

In examining each PDF release by Congress, we noticed that many ads follow a theme in when they were purchased and posted on Facebook. The one above, for instance, seems to follow a common age demographic we observed for many of the ads (18 – 65+).

We also noticed that a significant portion of the ads

The following three ads, for example — which ran after Donald Trump was elected — all contain the same copy. However, each one contains different targeting information.

0004790.jpg?t=1526105585958&width=600&name=P(1)0004790.jpg)

0004789-1.jpg?t=1526105585958&width=600&name=P(1)0004789-1.jpg)

0004788.jpg?t=1526105585958&width=600&name=P(1)0004788.jpg)

The first two are both targeted to users within 25 miles of Atlanta, GA, but the first one contains slightly more criteria under interests.

The third one appears to be targeted to the same interests as the first, but has a broader geographical range of the entire U.S.

By our analysis, these ads and were purchased in bulk over the course of each quarter between 2015 and 2017. The reason for that, most likely, was likely to maximize each ad’s impressions and increase the chances of sneaking through Facebook’s News Feed algorithm.

If 15 ads in a group of 20 on the same topic are intercepted by Facebook, for example, five would still be seen by Facebook users.

That could explain why the nearly 3,400 purchased ads also had such contrasting performance and impression numbers, according to the details released by the HPSCI Minority.

While some ads received more than half a million impressions, others promoting the same page — with the same copy — received zero.

The Impact, and Facebook’s Response

What’s particularly interesting — and perhaps troubling — about the nature of these ads, is the degree to which they leveraged Facebook’s already built-in targeting tools.

As far as we’ve been told, these ads weren’t necessarily strategically created or conceptualized based on information that was improperly obtained, as per the Cambridge Analytica scandal earlier this year. Instead, they were created and targeted using the same ad customization criteria available to all advertisers: age, location, interests, etcetera.

That’s likely part of the motivation behind Facebook’s new labeling and verification standards. Shortly after these documents were released by the HPSCI Minority, the social network released its own statement in which it reiterated the measures it’s taking to prevent a repeated weaponization of its platform.

“This will never be a solved problem because we’re up against determined, creative and well-funded adversaries,” the statement reads. “But we are making steady progress.”

Among these changes

“The full picture is astonishing,” says HubSpot Social Media Editor Henry Franco. “It’s reassuring to see Facebook taking some steps to improve its influence on elections and politics, but it’s also clear that the platform in 2016 was an open book for manipulating popular opinion for anyone with the time, resources, and commitment to get the job done.”

That picture still has yet to come completely into focus. The U.S. Special Counsel investigation into potential election interference is ongoing, and as the HPSCI Minority, some of the content in question has yet to be seen by the public.

“We will continue to work with Facebook and other tech companies,” Schiff said in his

Deje su comentario